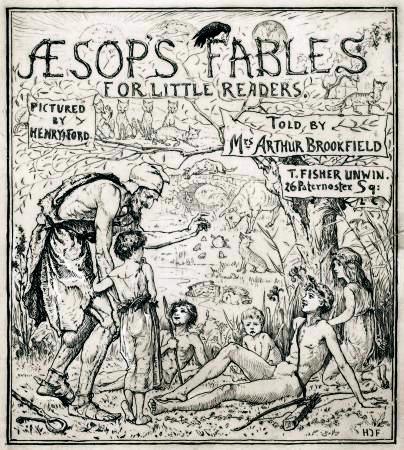

A source of the collections of the fables from Aesop: the collection of Demetrius of Phalerum

From the seventeenth century, when the edition of La Fontaine's Fables opens up a new period of editions and scholarship on the fable, until the most recent twentieth century scholarship, the ideas about the function of fable already expressed by Greek thinkers seem to have remained intact.

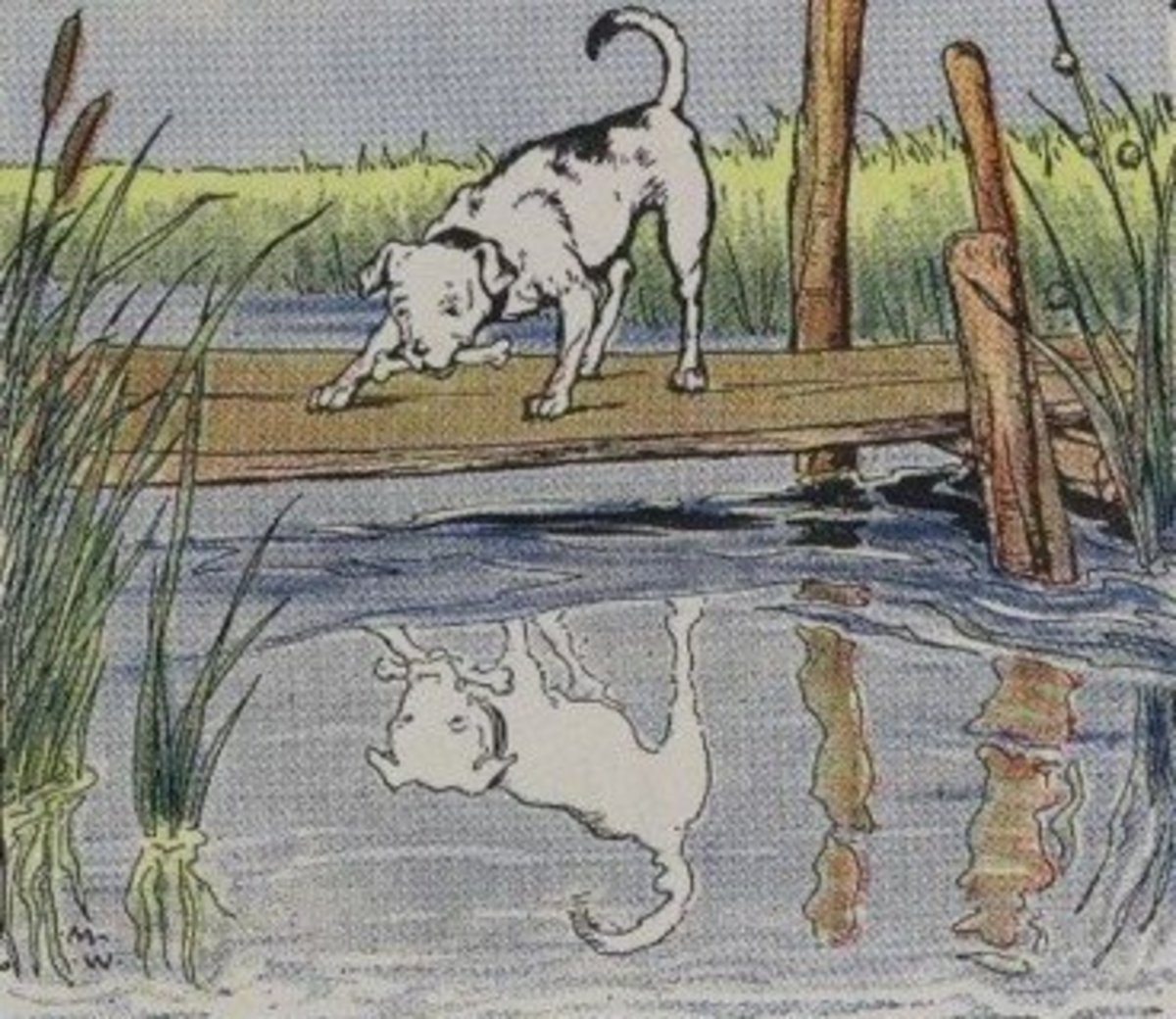

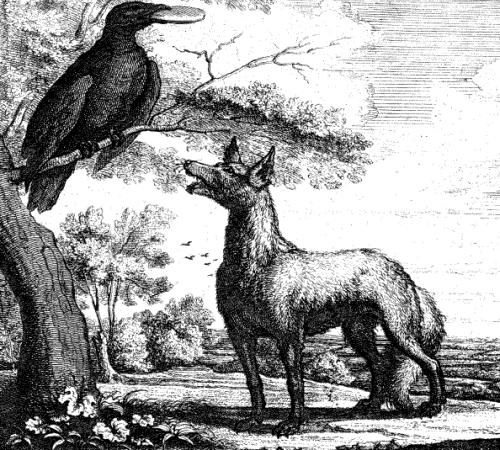

Our idea of the fable comes, in fact, from the collections of La Fontaine and his continuers starting from the 17th century, who mainly collected fables with animals taking part. In its turn, this theme is a reduction of that of its models, the ancient collections of Aesopic fables. In fact, these model collections contain more than animalistic fables (and fables with plants involved); they also include others in which stories are narrated about Gods or men, which may qualify either as myths or anecdotes, or else as tales, short stories etc. The continued indecision in Greek attempts to denominate the genre that we call "the fable" demonstrates that it was not easy to establish the bounds either of its content or of its form; and that there continued to be an awareness of the difficulties involved in delimiting it with respect to other closely related genres. We must note that the fable is one of the literary genres that are not denominated using a Greek word, though it very definitely comes from the Greeks. This paradox is explained precisely by the variations in the Greek terminology used to denote it, as well as by the fact that the most frequent Greek term, Aisopeioi logoi, consists of two words, which is not very convenient; not to mention the fact that the term logos is ambiguous and that it is frequent replaced by another term, mythos, myth. Both words were initially partly synonymous: the senses of "word", "saying", "story", "myth", "fable", "speech" etc. were present in both; and in principle there was no relation with the theme of the historical or fictitios, true or false character of a story. After, logos acquires a wider semantic space, and so it includes "calculation", "thought": Logos is the form and the content of language at the same time.

In Latin, there is the term fabula that can mean any narration or story, but it also means "conversation", and above all, it frequently refers to the myth and to any fabulous or poetic story. Fabula was a vague term in Latin, which served to neutralize the difference or opposition between the Greek terms logos and mythos, but it needed the term Aesopiae, by Aesop, to make it specific.

As I have stated above, our idea of the fable as an animalistic genre comes from certain collections of the modern era: those of La Fontaine, Iriarte and Samaniego, among others. In effect, starting from the 17th and 18th centuries, these collections created the modern idea of the fable. Yet this is not so in the ancient collections, to which I refer: in spite of the tendency towards a separation between the animalistic fable and the anecdote, story, novel, maxim, joke etc., the truth is that in the ancient collections that have reached us, all these elements appear mixed with animalistic fable. This original absence of distinction is based on the fact that the animalistic fable and these other subspecies evidently performed a parallel, if not identical, function to the use of the fable as an "exemplum", which, as we know, predates the collections. This is the case in Phaedrus, Babrius and the Anonymous Greek Fables, the three most extensive collections that have reached us. And it is also undoubtedly the case, judging by what we can infer, in the oldest collection of Greek fables, the source of the later Greek and Latin fables, that of Demetrius of Phalerum, at the end of the 4th century BC, that is the first European collection of Aesopic fables ever to be made. Demetrius, who was tyrant of Athens from 317 to 307 BC and a renowned philosopher, who was the founder of the Alexandria library, collected together all the fables he could find under the title of Aesopic Tales; this collection, running probably to some 200 fables, after being interpolated and edited by the alexandrine grammarians, was turned into neat Latin iambics by Phaedrus. As the modern Aesop is mainly derived from Phaedrus, the answer to the question "who wrote Aesop?" is simple: "Demetrius Phalereus".

If in his collection he gathered together material that is heterogeneous, from the viewpoint of those who consider that fables are only animal fables, this means that for him (and for the ancients in general) the concept of the fable was broader. Therefore, if, under the name of "Collection of Aesopic fables", Demetrius collected together material that later continued to occupy subsequent collections, this was because this material was seen by him as being homogeneous. (This also applies to the Medieval collections, including those of oriental origin or influence: the animalistic and the non-animalistic appear always mixed together).

During his time, in the 4th century BC, Aesopic themes existed within two traditions, the oral and the literary. The oral tradition included, on one hand, the legend of Aesop, plus certain themes such as the Phrygian homeland of Aesop or his stay on Samos; on the other hand, it consisted of loose fables that could have been used as exempla at the banquet and on various occasions. In fact, any animalistic fable, fictitious anecdote, aetiological or satirical myth, possibly even any other proverb, joke etc. was attributed to Aesop, described as "logos of Aesop". Alongside this oral tradition, there also existed an extensive literary tradition. Now, in the Hellenistic Age, Aesopic literature entered a new phase: on one hand, a life of Aesop was written, which included the elements of the previous legend plus other ones and contained proverbs, solutions to problems and oracles etc.; on the other hand, there arose many collections of fables, that is to say, agonal, situation and actiological fables.

What Demetrius Phalereus did was basically to collect together, putting them into prose, a series of fables that the Greek writers had used in isolation as exempla; he gathered the fables and presented them loose, without their setting, not as exempla, then, but as the items in a collection. We must consider that Demetrius Phalereus neither improvised nor lacked authority: in association with other peripatetics, such as Theophrastus, Dicaearchus, Aristoxenus etc. he continuated the work of Aristotle as the founder of the history of Greek literature. At the same time he fits within a tendency, one very in vogue at that time, of gathering together in collections literary and documentary items which, until then, remained isolated or were part of more extensive works (this was also one of the causes for the construction of the great library of Alexandria, in which all the texts of all times and traditions were gathered). Given the correspondence of the formulas and compositional schemes, as well as of the themes, between the Classical fable- that of the Socratics (it is generally recognized that the Socratics' interest in the fable, a pratical interest insofar as they used it in their teachings, undoubtedly influenced both Demetrius' decision to compose this work and his way of doing so)- and the older stratum of the fables of the collections of the Roman Age, it can be deduced that Demetrius did not introduce too many innovations. He restricted himself to drafting the fables of the Greek literature in prose form, in accordance with the schemes that had been imposed over time in the fable.

He made his selection according to a criterion that was widespread in the 5th and 4th centuries as to what the Aesopic fable was, following the model of the prosaic fable of the Socratics and as far as possible reducing the ancient iambic fable to fit this model. By doing this he makes a work that is partly original, at least as regards the detail of the composition and the style, but also as regards the selection of fables and the fabulization of different materials. His collection of fables was comparable, then, to those of myths or romances- the question of whether the central interest was documentary or literary is not very significant. The scope of this edition, however, might have followed Aristotle's theory on the use of fables as paradeigmata, examples, and it may have constituted a collection of materials for future use by orators and writers who wished to illustrate their arguments with a fable, as Socrates and Plato did: in fact, in ancient times, the nature of the fable was a wise mix of all this characteristics such as examples, moral teachings, poetry and charm of literature, entertainment and delight both for children and adults, cultural heritage of Greece and of the Hellenistic empires- means to educate children to the right moral behaviour- if it was not so, why then a politician, a philosopher and a great erudite and scholar, as Demetrius of Phalerus was, wrote a collection of fables, among his very vaste literary production that included almost texts on politics, moral and ethic, history and philosophy?